History Of Bristol on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At some time after the

At some time after the

archa

was established in the city, without which Jews would not have been legally allowed to conduct business. In 1210, all Jewish householders in England were imprisoned in Bristol and a hefty levy of 60,000 or 66,000 marks was imposed on them. During the

By the 13th century Bristol had become a busy port. Woollen cloth became its main export during the fourteenth to fifteenth century, while wine from

By the 13th century Bristol had become a busy port. Woollen cloth became its main export during the fourteenth to fifteenth century, while wine from  The end of the

The end of the

Bristol was made a

Bristol was made a

The long passage up the heavily tidal Avon Gorge, which had made the port highly secure during the Middle Ages, had become a liability which the construction of a new "

The long passage up the heavily tidal Avon Gorge, which had made the port highly secure during the Middle Ages, had become a liability which the construction of a new " The new middle class, led by those who agitated against the slave trade, in the city began to engage in charitable works. Notable were Mary Carpenter, who founded

The new middle class, led by those who agitated against the slave trade, in the city began to engage in charitable works. Notable were Mary Carpenter, who founded

The British and Colonial Aeroplane Company, which later became the

The British and Colonial Aeroplane Company, which later became the

Bristol History

Bristol Past

*

History of Bristol Past & Present

Photographic Record of Bristol's PastFamous Bristol Infographic

{{DEFAULTSORT:History of Bristol

Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

is a city

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

with a population of nearly half a million people in south west England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, situated between Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

and Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of Gl ...

on the tidal River Avon. It has been among the country's largest and most economically and culturally important cities for eight centuries. The Bristol area has been settled since the Stone Age and there is evidence of Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

occupation. A mint was established in the Saxon burgh of ''Brycgstow'' by the 10th century and the town rose to prominence in the Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

era, gaining a charter and county status in 1373. The change in the form of the name 'Bristol' is due to the local pronunciation of 'ow' as 'ol'.

Maritime connections to Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

, western France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

brought a steady increase in trade in wool, fish, wine and grain during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

. Bristol became a city in 1542 and trade across the Atlantic developed. The city was captured by Royalist troops and then recaptured for Parliament during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. During the 17th and 18th centuries the transatlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

and the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

brought further prosperity. Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_ NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style"> ...

, MP for Bristol, supported the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

and free trade. Prominent reformers such as Mary Carpenter

Mary Carpenter (3 April 1807 – 14 June 1877) was an English educational and social reformer. The daughter of a Unitarian minister, she founded a ragged school and reformatories, bringing previously unavailable educational opportunitie ...

and Hannah More

Hannah More (2 February 1745 – 7 September 1833) was an English religious writer, philanthropist, poet and playwright in the circle of Johnson, Reynolds and Garrick, who wrote on moral and religious subjects. Born in Bristol, she taught at a ...

campaigned against the slave trade.

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the construction of a floating harbour, advances in shipbuilding and further industrialisation with the growth of the glass, paper, soap and chemical industries aided by the establishment of Bristol as the terminus of the Great Western Railway by I. K. Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "on ...

. In the early 20th century, Bristol was in the forefront of aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines ...

manufacture and the city had become an important financial centre and high technology hub by the beginning of the 21st century.

Pre-Norman

Palaeolithic and Iron Age

There is evidence of settlement in the Bristol area from thepalaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός ''palaios'', "old" and λίθος '' lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone to ...

era, with 60,000-year-old archaeological finds at Shirehampton

Shirehampton is a district of Bristol in England, near Avonmouth, at the northwestern edge of the city.

It originated as a separate village, retains a High Street with a parish church and shops, and is still thought of as a village by many of it ...

and St Annes

Lytham St Annes () is a seaside town in the Borough of Fylde in Lancashire, England. It is on the Fylde coast, directly south of Blackpool on the Ribble Estuary. The population at the 2011 census was 42,954. The town is almost contiguous wi ...

. Stone tools made from flint, chert, sandstone and quartzite have been found in terraces of the River Avon, most notably in the neighbourhoods of Shirehampton and Pill

Pill or The Pill may refer to:

Drugs

* Pill (pharmacy), referring to anything small for a specific dose of medicine

* "The Pill", a general nickname for the combined oral contraceptive pill

Film and television

* ''The Pill'' (film), a 2011 fil ...

. There are Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

hill fort

A hillfort is a type of earthwork used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Some were used in the post-Roma ...

s near the city, at Leigh Woods

Leigh Woods is a area of woodland on the south-west side of the Avon Gorge, close to the Clifton Suspension Bridge, within North Somerset opposite the English city of Bristol and north of the Ashton Court estate, of which it formed a part. St ...

and Clifton Down

Clifton Down is an area of public open space in Bristol, England, north of the village of Clifton. With its neighbour Durdham Down to the northeast, it constitutes the large area known as The Downs, much used for leisure including walking and ...

on either side of the Avon Gorge

The Avon Gorge () is a 1.5-mile (2.5-kilometre) long gorge on the River Avon in Bristol, England. The gorge runs south to north through a limestone ridge west of Bristol city centre, and about 3 miles (5 km) from the mouth of the ...

, and at Kingsweston

Kingsweston was a ward of the city of Bristol. The three districts in the ward wer Coombe Dingle, Lawrence Weston and Sea Mills. The ward takes its name from the old district of Kings Weston (usually spelt in two words), now generally considere ...

, near Henbury

Henbury is a suburb of Bristol, England, approximately north west of the city centre. It was formerly a village in Gloucestershire and is now bordered by Westbury-on-Trym to the south; Brentry to the east and the Blaise Castle Estate, Blaise Ha ...

. Bristol was at that time part of the territory of the Dobunni

The Dobunni were one of the Iron Age tribes living in the British Isles prior to the Roman conquest of Britain. There are seven known references to the tribe in Roman histories and inscriptions.

Various historians and archaeologists have examined ...

. Evidence of Iron Age farmsteads has been found at excavations throughout Bristol, including a settlement at Filwood. There are also indications of seasonal occupation of the salt marshes at Hallen on the Severn

, name_etymology =

, image = SevernFromCastleCB.JPG

, image_size = 288

, image_caption = The river seen from Shrewsbury Castle

, map = RiverSevernMap.jpg

, map_size = 288

, map_c ...

estuary.

Roman era

During theRoman era

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

there was a settlement named ''Abona'' at the present Sea Mills; this was important enough to feature in the 3rd-century Antonine Itinerary

The Antonine Itinerary ( la, Itinerarium Antonini Augusti, "The Itinerary of the Emperor Antoninus") is a famous ''itinerarium'', a register of the stations and distances along various roads. Seemingly based on official documents, possibly ...

which documents towns and distances in the Roman empire, and was connected to Bath by a road

A road is a linear way for the conveyance of traffic that mostly has an improved surface for use by vehicles (motorized and non-motorized) and pedestrians. Unlike streets, the main function of roads is transportation.

There are many types of ...

. Archaeological excavations at ''Abona'' have found a street pattern, shops, cemeteries and wharves, indicating that the town served as a port. Another settlement at what is now Inns Court, Filwood, had possibly developed from earlier Iron Age farmsteads. There were also isolated villas and small settlements throughout the area, notably Kings Weston Roman Villa

Kings Weston Roman Villa is a Roman villa in Lawrence Weston in the north-west of Bristol (). The villa was discovered during the construction of the Lawrence Weston housing estate in 1947. Two distinct buildings (Eastern and Western) were disco ...

and another at Brislington.

Saxon era

A minster was founded in the 8th century atWestbury on Trym

Westbury on Trym is a suburb and council ward in the north of the City of Bristol, near the suburbs of Stoke Bishop, Westbury Park, Henleaze, Southmead and Henbury, in the southwest of England.

With a village atmosphere, the place is partly ...

and is mentioned in a charter of 804.

In 946 an outlaw named Leof killed Edmund I

Edmund I or Eadmund I (920/921 – 26 May 946) was King of the English from 27 October 939 until his death in 946. He was the elder son of King Edward the Elder and his third wife, Queen Eadgifu, and a grandson of King Alfred the Great. After ...

in a brawl at a feast in the royal palace at Pucklechurch

Pucklechurch is a large village and civil parish in South Gloucestershire, England. It has a current population of about 3000. The village dates back over a thousand years and was once the site of a royal hunting lodge, as it adjoined a large fo ...

, which lies about six miles from Bristol. The town of Bristol was founded on a low hill between the rivers Frome

Frome ( ) is a town and civil parish in eastern Somerset, England. The town is built on uneven high ground at the eastern end of the Mendip Hills, and centres on the River Frome. The town, about south of Bath, is the largest in the Mendip d ...

and Avon at some time before the early 11th century. The main evidence for this is a coin of Aethelred issued c. 1010. This shows that the settlement must have been a market town and the name ''Brycg stowe'' indicates "place by the bridge". It is believed that the '' Bristol L'' (the tendency for the local accent to add a letter L to the end of some words) is what changed the name ''Brycg stowe'' to the current name ''Bristol''.

It appears that St Peter's church, the remains of which stand in modern Castle Park, may have been another minster, possibly with 8th-century origins. By the time of Domesday

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

the church held three hides of land, which was a sizeable holding for a mere parish church. The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alf ...

'' records that in 1052 Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson ( – 14 October 1066), also called Harold II, was the last crowned Anglo-Saxon English king. Harold reigned from 6 January 1066 until his death at the Battle of Hastings, fighting the Norman invaders led by William the C ...

took ship to ''Brycgstow'' and later in 1062 he took ships from the town to subdue the forces of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn ( 5 August 1063) was King of Wales from 1055 to 1063. He had previously been King of Gwynedd and Powys in 1039. He was the son of King Llywelyn ap Seisyll and Angharad daughter of Maredudd ab Owain, and the great-gre ...

of Wales, indicating the status of the town as a port.

''Brycg stowe'' was a major centre for the Anglo-Saxon slave trade. Men, women and children captured in Wales or northern England were traded through Bristol to Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

as slaves. From there the Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

rulers of Dublin would sell them on throughout the known world. The Saxon bishop of Worcester, Wulfstan, whose diocese included Bristol, preached against the trade regularly and eventually it was forbidden by the crown, though it carried on in secret for many years.

Middle Ages

Norman era

At some time after the

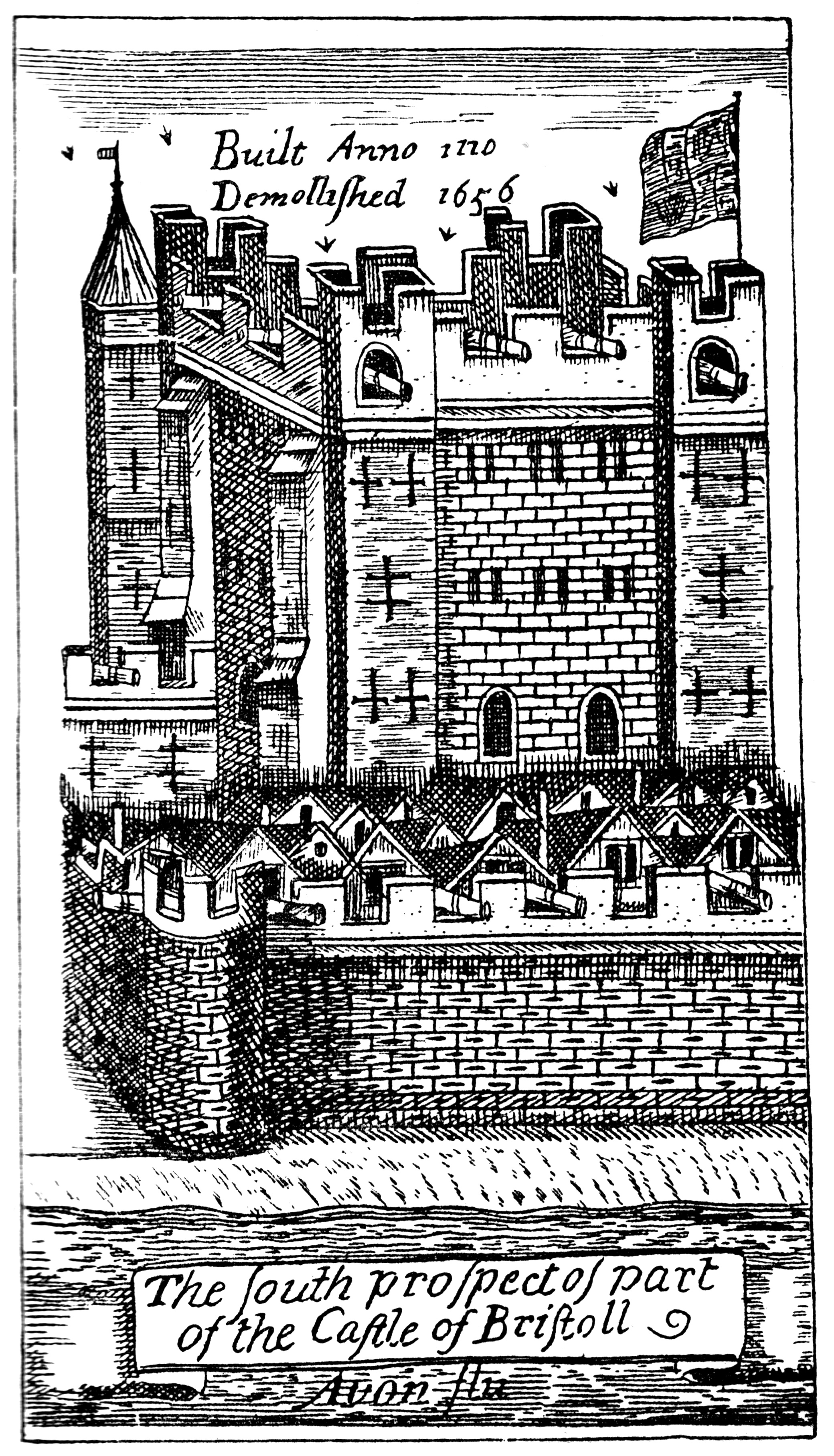

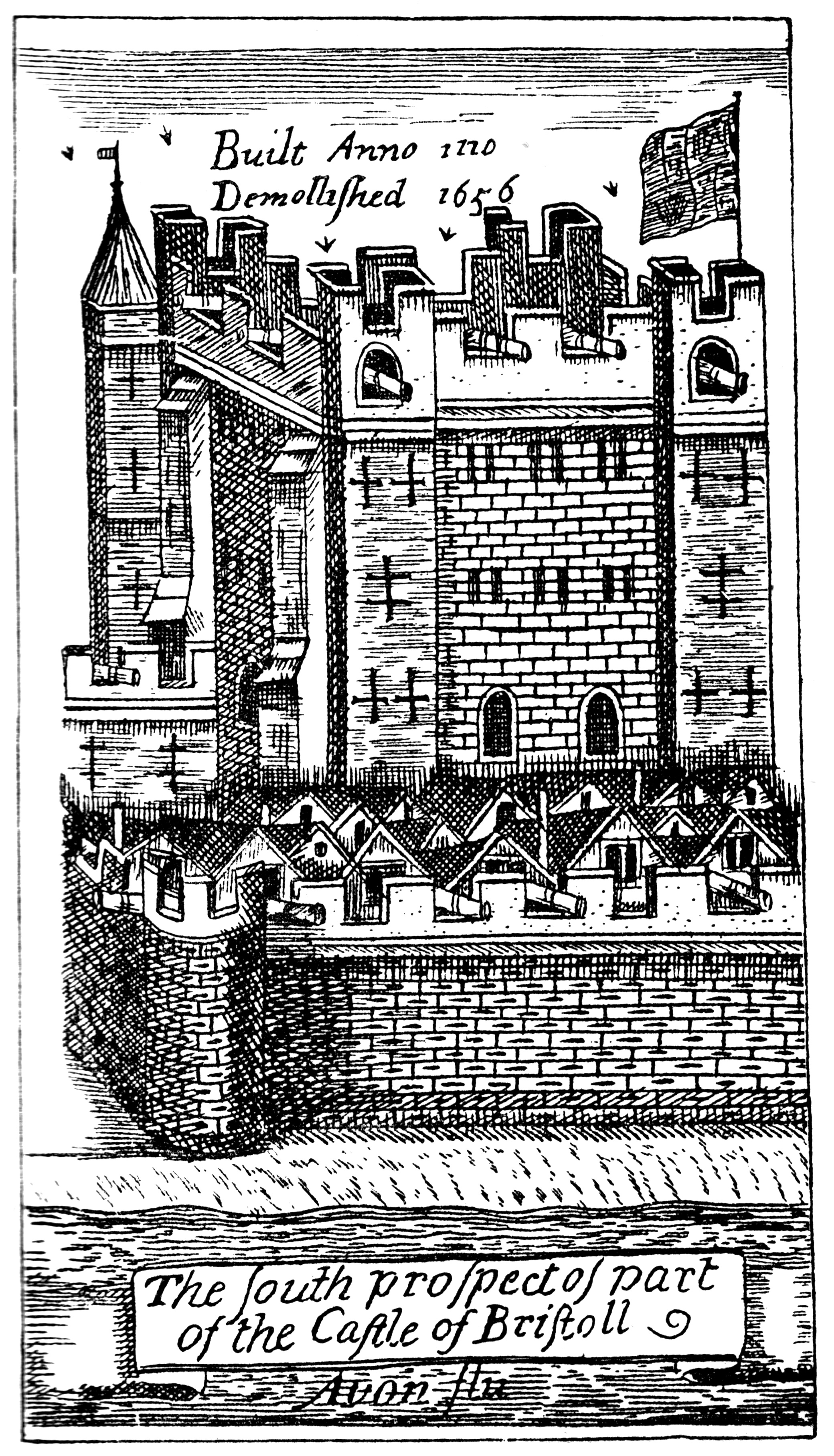

At some time after the Norman conquest of England

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, Duchy of Brittany, Breton, County of Flanders, Flemish, and Kingdom of France, French troops, ...

in 1066 a motte-and-bailey

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. Relatively easy to ...

was erected on the present site of Castle Park. Bristol was held by Geoffrey de Montbray

Geoffrey de Montbray (Montbrai, Mowbray) (died 1093), bishop of Coutances ( la, Constantiensis), also known as Geoffrey of Coutances, was a Norman nobleman, trusted adviser of William the Conqueror and a great secular prelate, warrior and adminis ...

, Bishop of Countances, one of the knights

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

who accompanied William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

. William ordered stone castles to be built so it is likely that the first parts of Bristol Castle

Bristol Castle was a Norman castle built for the defence of Bristol. Remains can be seen today in Castle Park near the Broadmead Shopping Centre, including the sally port. Built during the reign of William the Conqueror, and later owned by Rob ...

were built by Geoffrey in his reign. After the Conqueror's death (1087), Geoffrey joined the rebellion against William Rufus

William II ( xno, Williame; – 2 August 1100) was King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Normandy and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales. The third so ...

. Using Bristol as his headquarters, he burned Bath and ravaged Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

before submitting to Rufus. He eventually returned to Normandy and died at Coutances in 1093.

Rufus created the Honour of Gloucester, which included Bristol, from his mother Queen Matilda's estates and granted it to Robert Fitzhamon

Robert Fitzhamon (died March 1107), or Robert FitzHamon (literally, 'Robert, son of Hamon'), Seigneur de Creully in the Calvados region and Torigny in the Manche region of Normandy, was the first Norman feudal baron of Gloucester and the Norma ...

.

Fitzhamon enlarged and strengthened Bristol castle and in the latter years of the 11th century conquered and subdued much of south and west Wales. His daughter Mabel was married in 1114 to Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the No ...

's bastard son Robert of Caen. Her dowry was a large part of her father's Gloucestershire and Welsh estate and Robert of Caen became the first Earl of Gloucester, c. 1122. He is believed to have been responsible for completing Bristol castle.

In 1135 Henry I died and the Earl of Gloucester rallied to the support of his sister Matilda

Matilda or Mathilda may refer to:

Animals

* Matilda (chicken) (1990–2006), World's Oldest Living Chicken record holder

* Matilda (horse) (1824–1846), British Thoroughbred racehorse

* Matilda, a dog of the professional wrestling tag-team The ...

against Stephen of Blois

Stephen (1092 or 1096 – 25 October 1154), often referred to as Stephen of Blois, was King of England from 22 December 1135 to his death in 1154. He was Count of Boulogne ''jure uxoris'' from 1125 until 1147 and Duke of Normandy from 1135 unt ...

who had seized the throne on Henry's death. Stephen attempted to lay siege to Robert at Bristol in 1138 but gave up the attempt as the castle appeared impregnable. When Stephen was captured in 1141 he was imprisoned in the castle, but when Robert was captured by Stephen's forces, Matilda was forced to exchange Stephen for Robert. Her son Henry, later to become Henry II of England

Henry II (5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189), also known as Henry Curtmantle (french: link=no, Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress, or Henry Plantagenet, was King of England from 1154 until his death in 1189, and as such, was the first Angevin king ...

, was kept safe in the castle, guarded and educated by his uncle Robert. The castle was later taken into royal hands, and Henry III spent lavishly on it, adding a barbican

A barbican (from fro, barbacane) is a fortified outpost or fortified gateway, such as at an outer fortifications, defense perimeter of a city or castle, or any tower situated over a gate or bridge which was used for defensive purposes.

Europe ...

before the main west gate, a gate tower, and magnificent hall.

The Earl of Gloucester had founded the Benedictine priory of St James in 1137. In 1140 St Augustine's Abbey was founded by Robert Fitzharding

Robert Fitzharding (c. 1095–1170) was an Anglo-Saxon nobleman from Bristol who was granted the feudal barony of Berkeley in Gloucestershire. He rebuilt Berkeley Castle, and founded the Berkeley family which still occupies it today. He was a wea ...

, a wealthy Bristolian who had loyally supported the Earl and Matilda in the war. As a reward for this support he would later be made Lord of Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

. The abbey was a monastery of Augustinian canons. In 1148 the abbey church was dedicated by the bishops of Exeter, Llandaff, and St. Asaph, and during Fitzharding's lifetime the abbey also built the chapter house

A chapter house or chapterhouse is a building or room that is part of a cathedral, monastery or collegiate church in which meetings are held. When attached to a cathedral, the cathedral chapter meets there. In monasteries, the whole communi ...

and gatehouse

A gatehouse is a type of fortified gateway, an entry control point building, enclosing or accompanying a gateway for a town, religious house, castle, manor house, or other fortification building of importance. Gatehouses are typically the mos ...

.

In 1172, following the subjugation of the ''Pale

Pale may refer to:

Jurisdictions

* Medieval areas of English conquest:

** Pale of Calais, in France (1360–1558)

** The Pale, or the English Pale, in Ireland

*Pale of Settlement, area of permitted Jewish settlement, western Russian Empire (179 ...

'' in Ireland, Henry II gave Bristolians the right to reside in and trade from Dublin.

The medieval Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

community of Bristol was one of the more important in England. The Jews of Bristol were accused in a blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mur ...

in 1183, but not many details are known. At the end of the 12th century, aarcha

was established in the city, without which Jews would not have been legally allowed to conduct business. In 1210, all Jewish householders in England were imprisoned in Bristol and a hefty levy of 60,000 or 66,000 marks was imposed on them. During the

Second Barons' War

The Second Barons' War (1264–1267) was a civil war in England between the forces of a number of barons led by Simon de Montfort against the royalist forces of King Henry III, led initially by the king himself and later by his son, the fut ...

, the city's archa was burned and the Jewish community was violently attacked. There was another attack in 1275, but without fatalities. The community was expelled with the rest of England's Jews in 1290. There is a surviving mikveh

Mikveh or mikvah (, ''mikva'ot'', ''mikvoth'', ''mikvot'', or (Yiddish) ''mikves'', lit., "a collection") is a bath used for the purpose of ritual immersion in Judaism to achieve ritual purity.

Most forms of ritual impurity can be purif ...

, Jewish ritual bath, from this time period now known as Jacob's Well

Jacob's Well ( ar, بِئْر يَعْقُوب, Biʾr Yaʿqūb; gr, Φρέαρ του Ιακώβ, Fréar tou Iakóv; he, באר יעקב, Beʾer Yaʿaqov), also known as Jacob's fountain and Well of Sychar, is a deep well constructed into ...

.

Later Middle Ages

By the 13th century Bristol had become a busy port. Woollen cloth became its main export during the fourteenth to fifteenth century, while wine from

By the 13th century Bristol had become a busy port. Woollen cloth became its main export during the fourteenth to fifteenth century, while wine from Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part o ...

and Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectur ...

, was the principal import. In addition the town conducted an extensive trade with the Anglo-Irish ports of southern Ireland, such as Waterford and Cork, as well as with Portugal. From about 1420–1480 the port also traded with Iceland, from which it imported a type of freeze-dried cod called 'stockfish'.

In 1147 Bristol men and ships had assisted in the siege of Lisbon

The siege of Lisbon, from 1 July to 25 October 1147, was the military action that brought the city of Lisbon under definitive Portuguese control and expelled its Moorish overlords. The siege of Lisbon was one of the few Christian victories of ...

, which led to that city's recapture from the Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

. A stone bridge was built across the Avon, c. 1247 and between the years of 1240 and 1247 a ''Great Ditch'' was constructed in St Augustine's Marsh to straighten out the course of the River Frome and provide more space for berthing ships.

Redcliffe and Bedminster were incorporated into the city in 1373. Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

proclaimed "that the town of Bristol with its suburbs and precincts shall henceforth be separate from the counties of Gloucester and Somerset and be in all things exempt both by land by sea, and that it should be a county by itself, to be called the county of Bristol in perpetuity." This meant that disputes could be settled in courts in Bristol rather than at Gloucester, or at Ilminster

Ilminster is a minster town and civil parish in the South Somerset district of Somerset, England, with a population of 5,808. Bypassed in 1988, the town now lies just east of the junction of the A303 (London to Exeter) and the A358 (Taunton to ...

for areas south of the Avon which had been part of Somerset. The city walls extended into Redcliffe and across the eastern part of the march which now became the ''Town Marsh''. The major surviving part of the walls is visible adjacent to the only remaining gateway under the tower of the Church of St John the Baptist.

By the mid-14th century Bristol is considered to have been England's third-largest town (after London and York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

), with an estimated 15–20,000 inhabitants on the eve of the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

of 1348–49. The plague inflicted a prolonged demographic setback, with the population estimated at between 10,000 and 12,000 during the 15th and 16th centuries.

One of the first great merchants of Bristol was William Canynge

William II Canynges (c. 1399–1474) was an English merchant and shipper from Bristol, one of the wealthiest private citizens of his day and an occasional royal financier. He served as Mayor of Bristol five times and as MP for Bristol thr ...

. Born c. 1399, he was five times mayor of the town and twice represented it as an MP. He is said to have owned ten ships and employed over 800 sailors.

In later life he became a priest and spent a considerable part of his fortune in rebuilding St Mary Redcliffe

St Mary Redcliffe is an Anglican parish church located in the Redcliffe district of Bristol, England. The church is a short walk from Bristol Temple Meads station. The church building was constructed from the 12th to the 15th centuries, and it ...

church, which had been severely damaged by lightning in 1446.

The end of the

The end of the Hundred Years War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of England and France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French throne between the English House of Plantagen ...

in 1453 meant that Britain, and thus Bristol, lost its access to Gascon wines and so imports of Spanish and Portuguese wines increased. Imports from Ireland included fish, hides and cloth (probably linen). Exports to Ireland included broadcloth, foodstuffs, clothing and metals.

It has been suggested that the decline of Bristol's Iceland trade for 'stockfish' (freeze dried cod) was a hard blow to the local economy, encouraging Bristol merchants to turn west, launching unsuccessful voyages of exploration in the Atlantic by 1480 in search of the phantom island

A phantom island is a purported island which was included on maps for a period of time, but was later found not to exist. They usually originate from the reports of early sailors exploring new regions, and are commonly the result of navigati ...

of Hy-Brazil

Brasil, also known as Hy-Brasil and several other variants, is a phantom island said to lie in the Atlantic Ocean west of Ireland. Irish myths described it as cloaked in mist except for one day every seven years, when it becomes visible but ...

. More recent research, however, has shown that the Iceland trade was never more than a minor part of Bristol's overseas trade and that the English fisheries off Iceland actually increased during the late 15th and 16th centuries. In 1487, when king Henry VII visited the city, the inhabitants complained about their economic decline. Such complaints, however, were not uncommon among corporations that wished to avoid paying taxes, or which hoped to secure concessions from the Crown. In reality, Bristol's customs accounts show that the port's trade was growing strongly during the last two decades of the fifteenth century. In great part this was due of the increase of trade with Spain.

Exploration

In 1497 Bristol was the starting point forJohn Cabot

John Cabot ( it, Giovanni Caboto ; 1450 – 1500) was an Italian navigator and explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England is the earliest-known European exploration of coastal North ...

's voyage of exploration to North America. For many years Bristol merchants had bought freeze-dried cod, called stockfish

Stockfish is unsalted fish, especially cod, dried by cold air and wind on wooden racks (which are called "hjell" in Norway) on the foreshore. The drying of food is the world's oldest known preservation method, and dried fish has a storage lif ...

, from Iceland for consumption in England. However the Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

, which was trying to control North Atlantic trade at this time, sought to cut off supplies to English merchants. It has often been suggested that this drove Bristol's merchants to look West for new sources of cod fish. On the other hand, while Bristol merchants did largely abandon Iceland in the late-15th century, Hull merchants continued to trade there. Moreover, recent research has shown that England's fisheries off Iceland actually grew significantly from the 1490s, albeit the centre for this activity shifted from Bristol to East Anglia. This makes it hard to sustain the argument that Bristol merchants were somehow 'pushed out' of Iceland.

In 1481 two local men, Thomas Croft and John Jay, sent off ships looking for the mythical island of ''Hy-Brasil

Brasil, also known as Hy-Brasil and several other variants, is a phantom island said to lie in the Atlantic Ocean west of Ireland. Irish myths described it as cloaked in mist except for one day every seven years, when it becomes visible but ...

''. There was no mention of the island being discovered but Croft was prosecuted for illegal exports of salt, on the grounds that, as a customs officer, he should not have engaged in trade. Professor David Beers Quinn, whose theories form the basis for a variety of popular histories, suggested that the explorers may have discovered the Grand Banks

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland are a series of underwater plateaus south-east of the island of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf. The Grand Banks are one of the world's richest fishing grounds, supporting Atlantic cod, swordf ...

off Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, waters rich in cod.

John Cabot

John Cabot ( it, Giovanni Caboto ; 1450 – 1500) was an Italian navigator and explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England is the earliest-known European exploration of coastal North ...

was sponsored by Henry VII on his voyage in 1497, looking for a new route to the Orient. Having discovered North America instead, on his return Cabot spoke of the great quantities of cod to be found near the new land. In 1498 Cabot set sail again from Bristol with an expedition of five ships and is believed to have never returned from this voyage, although recent research conducted at the University of Bristol

, mottoeng = earningpromotes one's innate power (from Horace, ''Ode 4.4'')

, established = 1595 – Merchant Venturers School1876 – University College, Bristol1909 – received royal charter

, type ...

, suggests that he might have.

From 1499 to 1508 a number of other expeditions were launched from Bristol to the 'New found land', the earliest being undertaken by William Weston. One of these, led by John Cabot's son, Sebastian Cabot, explored down the coast of North America until he was 'almost in the latitude of Gibraltar' and 'almost the longitude of Cuba'. This would suggest that he reached as far as the Chesapeake Chesapeake often refers to:

*Chesapeake people, a Native American tribe also known as the Chesepian

* The Chesapeake, a.k.a. Chesapeake Bay

*Delmarva Peninsula, also known as the Chesapeake Peninsula

Chesapeake may also refer to:

Populated plac ...

, close to what is now Washington D.C.

Early modern

Tudor and Stuart periods

Bristol was made a

Bristol was made a city

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

in 1542, with the former Abbey

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christian monks and nuns.

The conce ...

of St Augustine becoming Bristol Cathedral

Bristol Cathedral, the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, is the Church of England cathedral in the city of Bristol, England. Founded in 1140 and consecrated in 1148, it was originally St Augustine's Abbey but after the Dissolu ...

, following the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

. The Dissolution also saw the surrender to the king of all of Bristol's friaries and monastic hospitals, together with St James' Priory, St Mary Magdalen nunnery, a Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

abbey at Kingswood and the College at Westbury on Trym

Westbury on Trym is a suburb and council ward in the north of the City of Bristol, near the suburbs of Stoke Bishop, Westbury Park, Henleaze, Southmead and Henbury, in the southwest of England.

With a village atmosphere, the place is partly ...

. In the case of the friaries at Greyfriars and Whitefriars, the prior

Prior (or prioress) is an ecclesiastical title for a superior in some religious orders. The word is derived from the Latin for "earlier" or "first". Its earlier generic usage referred to any monastic superior. In abbeys, a prior would be l ...

s had fled before the arrival of the royal commissioners, and at Whitefriars a succession of departing priors had plundered the friary of its valuables. Although the commissioners had not been able to point to as much religious malpractice in Bristol as elsewhere, there is no record of Bristolians raising any objections to the royal seizures. In 1541 Bristol's civic leaders took the opportunity of buying up lands and properties formerly belonging to St Mark's Hospital, St Mary Magdalen, Greyfriars and Whitefriars for a total of a thousand pounds. Bristol thereby became the only municipality in the country which has its own chapel, at St Mark's.

Bristol Grammar School

Bristol Grammar School (BGS) is a 4–18 mixed, independent day school in Bristol, England. It was founded in 1532 by Royal Charter for the teaching of 'good manners and literature', endowed by wealthy Bristol merchants Robert and Nicholas Thorn ...

was established in 1532 by the Thorne family and in 1596 John Carr established Queen Elizabeth's Hospital

Queen Elizabeth's Hospital (also known as QEH) is an independent day school in Clifton, Bristol, England, founded in 1586. QEH is named after its original patron, Queen Elizabeth I. Known traditionally as "The City School", Queen Elizabeth's Hosp ...

, a bluecoat school charged with 'the education of poor children and orphans'.

Trade continued to grow: by the mid-16th century imports from Europe included, wine, olive oil, iron, figs and other dried fruits and dyes; exports included cloth (both cotton and wool), lead and hides. Many of the city's leading merchants were involved in smuggling at this time, illicitly exporting goods like foodstuffs and leather, while under-declaring imports of wine.

In 1574 Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

visited the city during her '' Royal Progress'' through the western counties. The city burgesses spent over one thousand pounds on preparations and entertainments, most of which was raised by special rate assessments. In 1577 the explorer Martin Frobisher

Sir Martin Frobisher (; c. 1535 – 22 November 1594) was an English seaman and privateer who made three voyages to the New World looking for the North-west Passage. He probably sighted Resolution Island near Labrador in north-eastern Canada ...

arrived in the city with two ships and samples of ore, which proved to be worthless. He also brought, according to Latimer "three ''savages'', doubtless ''Esqiumaux'', clothed in deerskins, but all of them died within a month of their arrival."

Bristol sent three ships to the Royal Navy fleet against the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

in 1588, and also supplied two levies of men to the defending land forces. Despite appeals to the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

no reimbursement was made for these supplies. The corporation also had to repair the walls and gates of the city. The castle had fallen into disuse in the late Tudor era, but the City authorities had no control over royal property and the precincts became a refuge for lawbreakers.

Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional fo ...

came to Bristol in June 1613 and was welcomed by the mayor Abel Kitchin. The visit featured a pageant on the river, with an English ship attacked by Turkish galleys, which the queen watched from the Canon's Marsh meadow near the Cathedral. An English victory was signalled by the release of six bladders of pig's blood poured out of the ship's scupper

A scupper is an opening in the side walls of a vessel or an open-air structure, which allows water to drain instead of pooling within the bulwark or gunwales of a vessel, or within the curbing or walls of a building.

There are two main kinds of s ...

holes.

English Civil War

In 1630 the city corporation bought the castle and when theFirst English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Anglo ...

broke out in 1642, the city took the Parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democracy, democratic government, governance of a sovereign state, state (or subordinate entity) where the Executive (government), executive derives its democratic legitimacy ...

side and partly restored the fortifications. However Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

troops under the command of Prince Rupert

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, (17 December 1619 (O.S.) / 27 December (N.S.) – 29 November 1682 (O.S.)) was an English army officer, admiral, scientist and colonial governor. He first came to prominence as a Royalist cavalr ...

captured Bristol on 26 July 1643, in the process causing extensive damage to both town and castle. The Royalist forces captured large amounts of booty and also eight armed merchant vessels which became the nucleus of the Royalist fleet. Workshops in the city became arms factories, providing muskets for the Royalist army.

In the summer of 1645, Royalist forces were defeated by the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

at the Battle of Langport

The Battle of Langport was a Parliamentarian victory late in the First English Civil War which destroyed the last Royalist field army and gave Parliament control of the West of England, which had hitherto been a major source of manpower, ra ...

, in Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

. Following further victories at Bridgwater

Bridgwater is a large historic market town and civil parish in Somerset, England. Its population currently stands at around 41,276 as of 2022. Bridgwater is at the edge of the Somerset Levels, in level and well-wooded country. The town lies alon ...

and Sherborne

Sherborne is a market town and civil parish in north west Dorset, in South West England. It is sited on the River Yeo, on the edge of the Blackmore Vale, east of Yeovil. The parish includes the hamlets of Nether Coombe and Lower Clatcombe. T ...

, Sir Thomas Fairfax

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron (17 January 161212 November 1671), also known as Sir Thomas Fairfax, was an English politician, general and Parliamentary commander-in-chief during the English Civil War. An adept and talented command ...

marched on Bristol. Prince Rupert returned to organise the defence of the city. The Parliamentary forces besieged the city and after three weeks attacked, eventually forcing Rupert to surrender on 10 September. The First Civil War ended the following year. There were no further military actions in Bristol during the second

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ...

and third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* Second#Sexagesimal divisions of calendar time and day, 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (d ...

civil wars. In 1656, Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

ordered the destruction of the castle.

Slave trade

William de la Founte, a wealthy Bristol merchant has been identified as the first recordedEnglish

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

slave traders. Of Gascon origin, in 1480 he was one of the four venturers granted a licence "to trade in any parts".

Renewed growth came with the 17th-century rise of England's American colonies and the rapid 18th-century expansion of Bristol's part in the "Triangular trade

Triangular trade or triangle trade is trade between three ports or regions. Triangular trade usually evolves when a region has export commodities that are not required in the region from which its major imports come. It has been used to offset t ...

" in Africans taken for slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

. Over 2000 slaving voyages were made by Bristol ships between the late 17th century and abolition in 1807, carrying an estimated half a million people from Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

to the Americas in brutal conditions. Average profits per voyage were seventy percent and more than fifteen per cent of the Africans transported died or were murdered on the Middle Passage

The Middle Passage was the stage of the Atlantic slave trade in which millions of enslaved Africans were transported to the Americas as part of the triangular slave trade. Ships departed Europe for African markets with manufactured goods (first ...

. Some slaves were brought to Bristol, from the Caribbean; notable among these were Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (, , ; 236/235–183 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, most notable as one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the best military com ...

, buried at Henbury

Henbury is a suburb of Bristol, England, approximately north west of the city centre. It was formerly a village in Gloucestershire and is now bordered by Westbury-on-Trym to the south; Brentry to the east and the Blaise Castle Estate, Blaise Ha ...

and Pero Jones brought to Bristol by slave trader and plantation owner John Pinney

John Pretor Pinney (1740 – 23 January 1818) was a plantation owner on the island of Nevis in the West Indies and was a sugar merchant in Bristol. He made his fortune from England’s demand for sugar. His Bristol residence is now the city ...

.

The slave trade and the consequent demand for cheap brass ware for export to Africa caused a boom in the copper and brass manufacturing industries of the Avon valley, which in turn encouraged the progress of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

in the area. Prominent manufacturers such as Abraham Darby Abraham Darby may refer to:

People

*Abraham Darby I (1678–1717) the first of several men of that name in an English Quaker family that played an important role in the Industrial Revolution. He developed a new method of producing pig iron with ...

and William Champion developed extensive works between Conham

Conham is a suburb of the city of Bristol in England. It lies near Hanham on the north bank of the River Avon just outside the city boundaries in South Gloucestershire

South Gloucestershire is a unitary authority area in the ceremonial c ...

and Keynsham which used ores from the Mendips

The Mendip Hills (commonly called the Mendips) is a range of limestone hills to the south of Bristol and Bath in Somerset, England. Running from Weston-super-Mare and the Bristol Channel in the west to the Frome valley in the east, the hills ...

and coal from the North Somerset coalfield. Water power from tributaries of the Avon drove the hammers in the brass batteries, until the development of steam power in the later 18th century. Glass, soap, sugar, paper and chemical industries also developed along the Avon valley.

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_ NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style"> ...

was elected as Whig Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

for Bristol in 1774 and campaigned for free trade, Catholic emancipation and the rights of the American colonists, but he angered his merchant sponsors with his detestation of the slave trade and lost the seat in 1780.

Anti-slavery campaigners, inspired by Non-conformist preachers such as John Wesley

John Wesley (; 2 March 1791) was an English people, English cleric, Christian theology, theologian, and Evangelism, evangelist who was a leader of a Christian revival, revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The soci ...

, started some of the earliest campaigns against the practice. Prominent local opponents of both the trade and the institution of slavery itself included Anne Yearsley, Hannah More

Hannah More (2 February 1745 – 7 September 1833) was an English religious writer, philanthropist, poet and playwright in the circle of Johnson, Reynolds and Garrick, who wrote on moral and religious subjects. Born in Bristol, she taught at a ...

,

Harry Gandey, Mary Carpenter

Mary Carpenter (3 April 1807 – 14 June 1877) was an English educational and social reformer. The daughter of a Unitarian minister, she founded a ragged school and reformatories, bringing previously unavailable educational opportunitie ...

, Robert Southey

Robert Southey ( or ; 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic school, and Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Southey began as a ra ...

, William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

and Samuel Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake P ...

. The campaign itself proved to be the beginning of movements for reform and women's emancipation

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

.

18th and 19th centuries

TheBristol Corporation of the Poor

The Bristol Corporation of the Poor was the board responsible for poor relief in Bristol, England when the Poor Law system was in operation. It was established in 1696 by the Bristol Poor Act.

The main promoter of the act was a merchant, John ...

was established at the end of the 17th century and a workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse'' ...

, to provide work for the poor and shelter for those needing charity, was established, adjacent to the Bridewell. John Wesley

John Wesley (; 2 March 1791) was an English people, English cleric, Christian theology, theologian, and Evangelism, evangelist who was a leader of a Christian revival, revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The soci ...

founded the very first Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

Chapel, The New Room in Broadmead in 1739, which is still in use in the 21st century. Wesley had come to Bristol at the invitation of George Whitfield

George Whitefield (; 30 September 1770), also known as George Whitfield, was an Anglican cleric and evangelist who was one of the founders of Methodism and the evangelical movement.

Born in Gloucester, he matriculated at Pembroke College at th ...

. He preached in the open air to miners and brickworkers in Kingswood and Hanham

Hanham is a suburb of Bristol. It is located in the south east of the city. Hanham is in the unitary authority of South Gloucestershire. It became a civil parish on 1 April 2003.

The post code area of Hanham is BS15. The population of this c ...

.

Kingswood is the site of a recent archaeological excavation (2014) which uncovered the diversity of artisans living in the area at the time.

Bristol Bridge

Bristol Bridge is a bridge over the floating harbour in Bristol, England. The floating harbour was constructed on the original course of the River Avon, and there has been a bridge on the site since long before the harbour was created by impou ...

, the only way of crossing the river without using a ferry, was rebuilt between 1764 and 1768. The earlier medieval bridge was too narrow and congested to cope with the amount of traffic that needed to use it. A toll was charged to pay for the works, and when, in 1793, the toll was extended for a further period of time the Bristol Bridge Riot ensued. 11 people were killed and 45 injured, making it one of the worst riots of the 18th century.

Competition from Liverpool from 1760, the disruption of maritime commerce through war with France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

(1793) and the abolition of the slave trade (1807) contributed to the city's failure to keep pace with the newer manufacturing centres of the North and Midlands. The cotton industry failed to develop in the city; sugar, brass and glass production went into decline. Abraham Darby left Bristol for Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called the Gorge.

This is where iron ore was first s ...

when his advanced ideas for iron production received no backing from local investors. Buchanan and Cossons cite "a certain complacency and inertia rom the prominent mercantile familieswhich was a serious handicap in the adjustment to new conditions in the Industrial Revolution period."

The long passage up the heavily tidal Avon Gorge, which had made the port highly secure during the Middle Ages, had become a liability which the construction of a new "

The long passage up the heavily tidal Avon Gorge, which had made the port highly secure during the Middle Ages, had become a liability which the construction of a new "Floating Harbour

Bristol Harbour is the harbour in the city of Bristol, England. The harbour covers an area of . It is the former natural tidal river Avon through the city but was made into its current form in 1809 when the tide was prevented from going out per ...

" (designed by William Jessop

William Jessop (23 January 1745 – 18 November 1814) was an English civil engineer, best known for his work on canals, harbours and early railways in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Early life

Jessop was born in Devonport, Devon, the ...

) in 1804–1809 failed to overcome. Nevertheless, Bristol's population (61,000 in 1801) grew fivefold during the 19th century, supported by growing commerce. It was particularly associated with the leading engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "one ...

, who designed the Great Western Railway between Bristol and London, two pioneering Bristol-built steamships, the SS Great Western

SS ''Great Western'' of 1838, was a wooden-hulled paddle-wheel steamship with sails the first steamship purpose-built for crossing the Atlantic, and the initial unit of the Great Western Steamship Company. She was the largest passenger ship in ...

and the SS Great Britain

SS ''Great Britain'' is a museum ship and former passenger steamship that was advanced for her time. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1845 to 1854. She was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859), for the Great W ...

, and the Clifton Suspension Bridge

The Clifton Suspension Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Avon Gorge and the River Avon, linking Clifton in Bristol to Leigh Woods in North Somerset. Since opening in 1864, it has been a toll bridge, the income from which provides fun ...

.

The new middle class, led by those who agitated against the slave trade, in the city began to engage in charitable works. Notable were Mary Carpenter, who founded

The new middle class, led by those who agitated against the slave trade, in the city began to engage in charitable works. Notable were Mary Carpenter, who founded ragged school

Ragged schools were charitable organisations dedicated to the free education of destitute children in 19th century Britain. The schools were developed in working-class districts. Ragged schools were intended for society's most destitute children ...

s and reformatories, and George Müller

George Müller (born Johann Georg Ferdinand Müller, 27 September 1805 – 10 March 1898) was a Christian evangelist and the director of the Ashley Down orphanage in Bristol, England. He was one of the founders of the Plymouth Brethren mov ...

who founded an orphanage

An orphanage is a Residential education, residential institution, total institution or group home, devoted to the Childcare, care of orphans and children who, for various reasons, cannot be cared for by their biological families. The parent ...

in 1836. Badminton School

Badminton School is an independent, boarding and day school for girls aged 3 to 18 years situated in Westbury-on-Trym, Bristol, England. Named after Badminton House in Clifton, Bristol, where it was founded, the school has been located at its ...

was started in Badminton House, Clifton in 1858 and Clifton College

''The spirit nourishes within''

, established = 160 years ago

, closed =

, type = Public schoolIndependent boarding and day school

, religion = Christian

, president =

, head_label = Head of College

, head ...

was established in 1862. University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies ...

, the predecessor of the University of Bristol

, mottoeng = earningpromotes one's innate power (from Horace, ''Ode 4.4'')

, established = 1595 – Merchant Venturers School1876 – University College, Bristol1909 – received royal charter

, type ...

, was founded in 1876 and the former Merchant Venturers Navigation School became the Merchant Venturers College in 1894. This later formed the nucleus of Bristol Polytechnic

The University of the West of England (also known as UWE Bristol) is a public research university, located in and around Bristol, England.

The institution was know as the Bristol Polytechnic in 1970; it received university status in 1992 and ...

, which in turn became the University of the West of England

The University of the West of England (also known as UWE Bristol) is a public research university, located in and around Bristol, England.

The institution was know as the Bristol Polytechnic in 1970; it received university status in 1992 and ...

.

The Bristol Riots of 1831 took place after the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

rejected the second Reform Bill

In the United Kingdom, Reform Act is most commonly used for legislation passed in the 19th century and early 20th century to enfranchise new groups of voters and to redistribute seats in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. ...

. Local magistrate Sir Charles Wetherall, a strong opponent of the Bill, visited Bristol to open the new Assize Courts and an angry mob chased him to the Mansion House in Queen Square. The Reform Act was passed in 1832 and the city boundaries were expanded for the first time since 1373 to include "Clifton, the parishes of St. James, St. Paul, St. Philip, and parts of the parishes of Bedminster and Westbury". The parliamentary constituencies

An electoral district, also known as an election district, legislative district, voting district, constituency, riding, ward, division, or (election) precinct is a subdivision of a larger state (a country, administrative region, or other poli ...

in the city were revised in 1885 when the original Bristol (UK Parliament constituency)

Bristol was a two-member constituency, used to elect members to the House of Commons in the Parliaments of England (to 1707), Great Britain (1707–1800) and the United Kingdom (from 1801). The constituency existed until Bristol was divided int ...

was split into four.

Bristol lies on one of the UK's lesser coalfield

A coalfield is an area of certain uniform characteristics where coal is mined. The criteria for determining the approximate boundary of a coalfield are geographical and cultural, in addition to geological. A coalfield often groups the seams of ...

s, and from the 17th century collieries

Coal mining is the process of resource extraction, extracting coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its Energy value of coal, energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use c ...

opened in Bristol, and what is now North Somerset and South Gloucestershire. Though these prompted the construction of the Somerset Coal Canal

The Somerset Coal Canal (originally known as the Somersetshire Coal Canal) was a narrow canal in England, built around 1800. Its route began in basins at Paulton and Timsbury, ran to nearby Camerton, over two aqueducts at Dunkerton, through a ...

, and the formation of the Bristol Miners' Association

The Bristol Miners' Association was a trade union representing coal miners in Bristol and Bedminster in England.

The union was founded in June 1889 with around 2,000 members. It recruited Northumberland miner William Whitefield as its first a ...

, it was difficult to make mining profitable, and the mines closed after nationalisation.

At the end of the 19th century the main industries were tobacco and cigarette manufacture, led by the dominant W.D. & H.O. Wills company, paper and engineering. The port facilities were migrating downstream to Avonmouth

Avonmouth is a port and outer suburb of Bristol, England, facing two rivers: the reinforced north bank of the final stage of the Avon which rises at sources in Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and Somerset; and the eastern shore of the Severn Estuar ...

and new industrial complexes were founded there.Modern history

The British and Colonial Aeroplane Company, which later became the

The British and Colonial Aeroplane Company, which later became the Bristol Aeroplane Company

The Bristol Aeroplane Company, originally the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company, was both one of the first and one of the most important British aviation companies, designing and manufacturing both airframes and aircraft engines. Notable a ...

, then part of the British Aircraft Corporation

The British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) was a British aircraft manufacturer formed from the government-pressured merger of English Electric Aviation Ltd., Vickers-Armstrongs (Aircraft), the Bristol Aeroplane Company and Hunting Aircraft in 1 ...

and finally BAE Systems

BAE Systems plc (BAE) is a British multinational arms, security, and aerospace company based in London, England. It is the largest defence contractor in Europe, and ranked the seventh-largest in the world based on applicable 2021 revenues. ...

, was founded by Sir George White, owner of Bristol Tramways

Bristol Tramways operated in the city of Bristol, England from 1875, when the Bristol Tramways Company was formed by Sir George White, until 1941 when a Luftwaffe bomb destroyed the main power supply cables.

History

The first trams in Brist ...

in 1910. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

production of the Bristol Scout

The Bristol Scout was a single-seat rotary-engined biplane originally designed as a racing aircraft. Like similar fast, light aircraft of the period it was used by the RNAS and the RFC as a " scout", or fast reconnaissance type. It was one o ...

and the Bristol F.2 Fighter

The Bristol F.2 Fighter is a British First World War two-seat biplane fighter and reconnaissance aircraft developed by Frank Barnwell at the Bristol Aeroplane Company. It is often simply called the Bristol Fighter, ''"Brisfit"'' or ''"Bif ...

established the reputation of the company. The main base at Filton

Filton is a town and civil parish in South Gloucestershire, England, north of Bristol. Along with nearby Patchway and Bradley Stoke, Filton forms part of the Bristol urban area and has become an overflow settlement for the city. Filton Church d ...

is still a prominent manufacturing site for BAE Systems in the 21st century. The Bristol Aeroplane Company's engine department became a subsidiary company Bristol Aero Engines, then Bristol Siddeley

Bristol Siddeley Engines Ltd (BSEL) was a British aero engine manufacturer. The company was formed in 1959 by a merger of Bristol Aero-Engines Limited and Armstrong Siddeley Motors Limited. In 1961 the company was expanded by the purchase of t ...

Engines; and were bought by Rolls-Royce Limited

Rolls-Royce was a British luxury car and later an aero-engine manufacturing business established in 1904 in Manchester by the partnership of Charles Rolls and Henry Royce. Building on Royce's good reputation established with his cranes, they ...

in 1966, to become Rolls-Royce plc

Rolls-Royce Holdings plc is a British multinational aerospace and defence company incorporated in February 2011. The company owns Rolls-Royce, a business established in 1904 which today designs, manufactures and distributes power systems for ...

which is still based at Filton. Shipbuilding in the city docks, predominately by Charles Hill & Sons

Charles Hill & Sons was a major shipbuilder based in Bristol, England, during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Background

Established in 1845 from the company Hilhouse, they specialised mainly in merchant and commercial ships, but also undertook th ...

, formerly Hilhouse

Hilhouse (also spelled ''Hillhouse'') was a shipbuilder in Bristol, England, who built merchantman and men-of-war during the 18th and 19th centuries. The company subsequently became Charles Hill & Sons in 1845.

The company, and its successor C ...

, remained important until the 1970s. Other prominent industries included chocolate manufacturers J. S. Fry & Sons and wine and sherry importers John Harvey & Sons

John Harvey & Sons is a brand (trading name) of a wine and sherry blending and merchant business founded by William Perry in Bristol, England in 1796. The business within 60 years of John Harvey joining had blended the first dessert sherry, d ...

.

Bristol City F.C.

Bristol City Football Club is a professional football club based in Bristol, England, which compete in the , the second tier of English football. They have played their home games at Ashton Gate since moving from St John's Lane in 1904. The ...

(formed in 1897) joined the Football League in 1901 and became runners up in the First Division in 1906 and losing FA Cup

The Football Association Challenge Cup, more commonly known as the FA Cup, is an annual knockout football competition in men's domestic English football. First played during the 1871–72 season, it is the oldest national football competi ...

finalists in 1909. Rivals Bristol Rovers F.C.